Tag: BMW

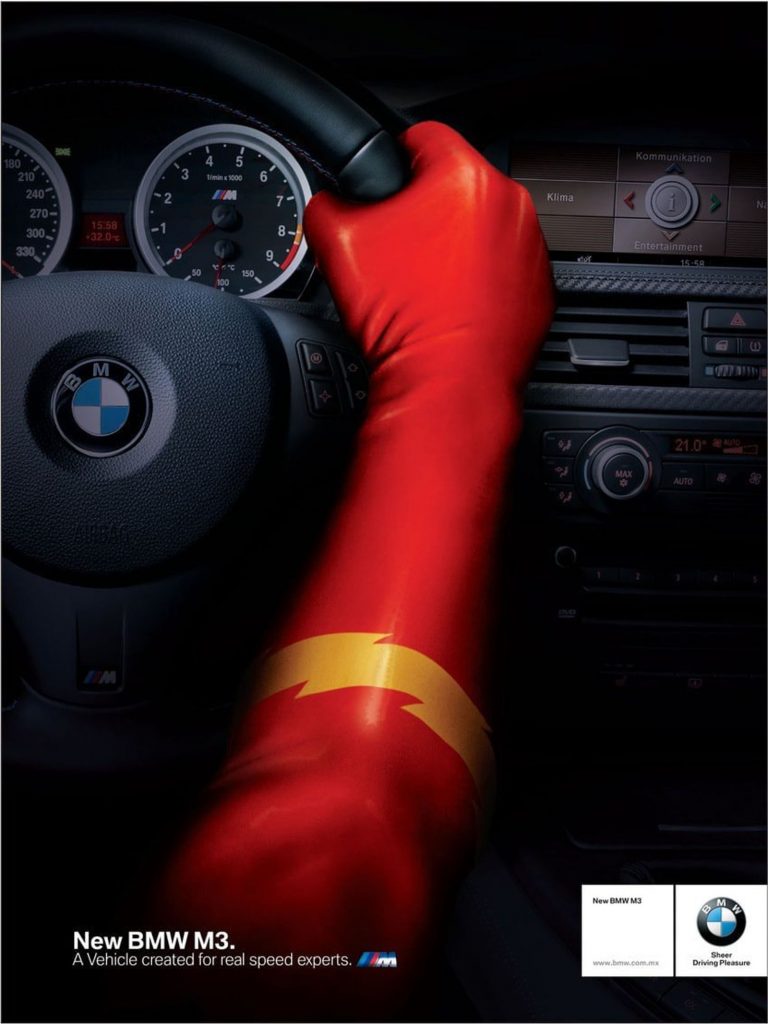

♦️ BMW M3 Created for Real Speed Experts

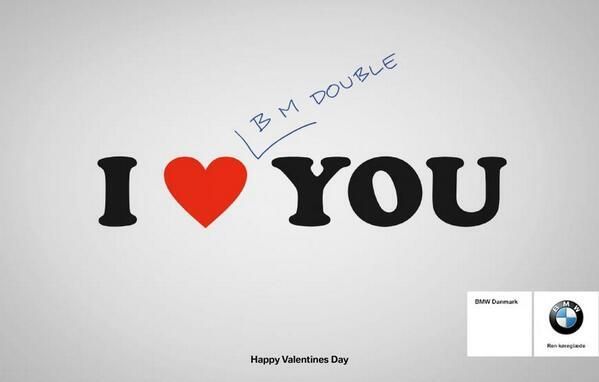

♦️ BMW That’s A Sign

💎 It’s better to express claims as facts (since facts are more believable than claims)

2. Since facts are more believable than claims, it’s better to express claims as facts.

In advertising, claim is often a euphemism for lie. Many of these euphemised lies are specially constructed to wiggle past lawyers and network censors. You can’t say your peanut butter has more peanuts, not without a notarised peanut count, but you can say someone will be a better mother if she serves it. At your arraignment all you have to do is plead Puffery. All charges are dropped. Puffery forgives everything. To lawyers and censors, it’s okay to lie as long as you lie on a grand enough scale. To everyone else, a lie is still a lie, and it’s almost always transparent. That’s why, instead of just asserting that BMW was a good investment, a BMW ad used the car’s high resale value to prove the point. And it did so, not by comparing the car to other cars but to other investments people in that target audience might make: “Last year a car outperformed 318 stocks on the New York Stock Exchange.”

Excerpt from: D&Ad Copy Book by D&AD

💎 On the secret behind the world’s first aspirational root vegetable (scarcity)

Scarcity is a great way to make something seem more attractive and valuable. The Blues Brothers famously played ‘for one night only’ and Bernd Pichetsrieder, the great BMW marketing guru insisted on ‘always selling one less than you can’.

This kind of strategy is sometimes called the ‘velvet rope’ – ‘you can’t come in’ often makes something that much more appealing. This was also the trick behind the story of how Frederick the Great turned Prussia into a potato eating nation – he insisted that no-one but the nobility could eat the potato. The ‘aspirational’ root vegetable? Believe it.

Excerpt from: Copy, Copy, Copy: How to Do Smarter Marketing by Using Other People’s Ideas by Mark Earls

💎 On how higher prices increase joy but not happiness (think about your car)

How much pleasure do you get from your car? Put it on a scale from 0 to 10. If you don’t own a car, then do the same for your house, your flat, your laptop, anything like that. Psychologists Norbert Schwarz, Daniel Kahneman and Jing Xu asked motorists this question and compared their responses with the monetary value of the vehicle. The result? The more luxurious the car, the more pleasure it gave the owner. A BMW 7 Series generates about fifty percent more pleasure than a Ford Escort. So far, so good: when somebody sinks a load f money in a vehicle, at least they felt a good return on their investment in the form of joy.

Now, let’s ask a slightly different question: how happy were you during your last car trip? The researchers posed the question too, and again compared the motorists’ answers with values of their cars. The result? No correlation. No matter how luxurious or how shabby the vehicle, the owners’ happiness ratings were all equally rock bottom.

Excerpt from: The Art of the Good Life: Clear Thinking for Business and a Better Life by Rolf Dobelli

💎 On confident branding (Renault versus Audi)

The third marker, I would say, is the most influential of all, yet hardly anyone spots it even though it is staring you in the face. This is the one that arises from Hegarty’s decision not to translate the slogan. By leaving the slogan in the original German he enabled the brand to occupy the position of being not just German, but being uncompromisingly German.

Most foreign cars in the 1980s tried to play down their foreign origins. And in order to demonstrate that their cars were “anglicised,” advertisers used English slogans in their advertising. BMW used the slogan “The Ultimate Driving Machine,” Renault in their 1992 Clio ad used “A certain Style,” and VW in their iconic Princess Diana Golf ad used “If only everything in life was as reliable as a Volkswagen.” But Audi, by sticking to their original German slogan, effectively gave out a super-confident message that their cars were German and proud of it, and that they were not prepared to compromise them by changing them in any way. If people wanted a hybrid adapted to their local market then they could buy one of the other marques, but if they wanted the real thing then they should buy an Audi.

Excerpt from: Seducing the Subconscious: The Psychology of Emotional Influence in Advertising by Robert Heath