Author: David Greenwood

💎 On originality lying on the far side of unoriginality

The final principle is that, more often than not, originality lies on the far side of unoriginality. The Finnish American photographer Arno Minkkinen dramatises this deep truth about the power of patience with a parable about Helsinki’, main bus station. There are two dozen platforms there, he explains, with several different bus lines departing from each one — and for the first part of its journey, each busk leaving from any given platform takes the same route through the city as all the others, making identical stops. Thinly’. each stop as representing one year of your career, Minkkinen advises photography students. You pick an artistic direction — perhaps you start working on platinum prints of nudes — and you begin to accumulate a portfolio of work. Three years (or bus stops) later, you proudly present it to the owner of a gallery. But you’re dismayed to be told that your pictures aren’t as original as you thought, because they look like knock-offs of the work of the photographer Irving Penn; Penn’s bus, it turns out, had been on the same route as yours. Annoyed at yourself for having wasted three years following somebody else’s path, you jump off that bus, hail a taxi, and return to where you started at the bus station. This time, you board a different bus, choosing a different genre of photography in which to specialise. But a few stops later, the same thing happens: you’re informed that your new body of work seems derivative, too. Back you go to the bus station. But the pattern keeps on repeating: nothing you produce ever gets recognised as being truly your own.

What’s the solution? ‘It’s simple,’ Minkkinen says. ‘Stay on the bus. Stay on the fucking bus.’ A little further out on their journeys through the city, Helsinki’s bus routes diverge, plunging off to unique destinations as they head through the suburbs and into the countryside beyond. That’s where the distinctive work begins. But it begins at all only for those who can muster the patience to immerse themselves in the earlier stage — the trial-and-error phase of copying others, learning new skills and accumulating experience.

Excerpt from: Four Thousand Weeks: Embrace your limits. Change your life by Oliver Burkeman

♦️ PolyBrite Super Absorbant

💎 How empathising can lead to immoral decisions

Take the following study carried out by another psychologist. In this experiment, a series of volunteers first heard the sad story of Sheri Summers, a ten-year-old suffering from a fatal disease. She’s on the waiting list for a life-saving treatment, but time’s running out. Subjects were told they could move Sheri up the waiting list, but they’re asked to be objective in their decision. Most people didn’t consider giving Sheri an advantage. They understood full well that every child on that list was sick and in need of treatment. Then came the twist. A second group of subjects was given the same scenario, but was then asked to imagine how Sheri must be feeling: Wasn’t it heartbreaking that this little girl was so ill? Turns out this single shot of empathy changed everything. The majority now wanted to let Sheri jump the line. If you think about it, that’s a pretty shaky moral choice. The spotlight on Sheri could effectively mean the death of other children who had been on the list longer.

Excerpt from: Humankind: A Hopeful History by Rutger Bregman

💎 Richard Curtis on misplaced views of realism humankind

`If you make a film about a man kidnapping a woman and chaining her to a radiator for five years — something that has happened probably once in history — it’s called searingly realistic analysis of society. If I make a film like Love Actually, which is about people falling in love, and there are about a million people falling in love in Britain today, it’s called a sentimental presentation of an unrealistic world.’

Richard Curtis

Excerpt from: Humankind: A Hopeful History by Rutger Bregman

♦️ Schick Free Your Skin

💎 Rather than trying to clear the decks, instead decline to clear the decks and instead focus on what’s of greatest consequence

In my days as a paid-up productivity geek, it was this aspect of the whole scenario that troubled me the most. Despite my thinking of myself as the kind of person who got things done, it grew painfully clear that the things I got done most diligently were the unimportant ones, while the important ones got postponed — either forever or until an imminent deadline forced me to complete them, to a mediocre standard and in a stressful rush. The email from my news-paper’s IT department about the importance of regularly changing my password would provoke me to speedy action, though I could have ignored it entirely. (The clue was in the subject line, where the words ‘PLEASE READ’ are generally a sign you needn’t bother reading what follows.) Mean-while, the long message from an old friend now living in New Delhi and research for the major article I’d been planning for months would get ignored, because I told myself that such tasks needed my full focus, which meant waiting until I had a good chunk of free time and fewer small-but-urgent tasks tugging at my attention. And so, instead, like the dutiful and efficient worker I was, I’d put my energy into clearing the decks, cranking through the smaller stuff to get it out of the way — only to discover that doing so took the Whole day, that the decks filled up again overnight anyway, and that the moment for responding to the New Delhi email or for researching the milestone article never arrived. One can waste years this way, systematically postponing precisely the things one cares about the most.

What’s needed instead in such situations, I gradually came to understand, is a kind of anti-skill: not the counter-productive strategy of trying to make yourself more efficient, but rather a willingness to resist such urges — to learn to stay with the anxiety of feeling overwhelmed, of not being on top of everything, without automatically responding by trying to fit more in. To approach your days in this fashion means, instead of clearing the decks, declining to clear the decks, focusing instead on what’s truly of greatest consequence while tolerating the discomfort of knowing that, as you do so, the decks will be filling up further, with emails and errands and other to-dos, many of which you may never get round to at all. You’ll sometimes still decide to drive yourself hard in an effort to squeeze more in, when circumstances absolutely re-quire it. But that won’t be your default mode, because you’ll no longer be operating under the illusion of one day making time for everything.

Excerpt from: Four Thousand Weeks: Embrace your limits. Change your life by Oliver Burkeman

♦️ WWF Extinction Cant Be Fixed

💎 On work expanding to fill the time available

The same goes for chores: in her book More Work for Mother, the American historian Ruth Schwarty Cowan shows that when housewives first got access to ‘laboursaving’ devices like washing machines and vacuum cleaners, no time was saved at all, because society’s standards of cleanliness simply rose to offset the benefits; now that you could return each of your husband’s shirts to a spotless condition after a single wearing, it began to feel like you should, to show how much you loved him. Work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion, the English humorist and historian C. Northcote Parkinson wrote in 1955, coining w became known as Parkinson’s law. But it’s not merely a joke and it doesn’t apply only to work. It applies to everything that needs doing. In fact, it’s the definition of what needs doing that expands to fill the time available.

Excerpt from: Four Thousand Weeks: Embrace your limits. Change your life by Oliver Burkeman

💎 There is no moment in the future when you’ll magically be done with everything

The same logic, Abel points out, applies to time. If you try to find time for your most valued activities by first dealing with all the other important demands on your time, in the hope that there’ll be some left over at the end, you’ll be disappointed. So if a certain activity really matters to you – a creative project, say, though it could just as easily be nurturing a relationship, or activism in the service of some cause – the only way to be sure it will happen is to do some of it today, no matter how little, and no matter how many other genuinely big rocks may be begging for your attention. After years of trying and failing to make time for her illustration work, by taming her to-do list and shuffling her schedule, Abel saw that her only viable option was to claim time instead – to just start drawing, for an hour or two, every day, and to accept the consequences, even if those included neglecting other activities she sincerely valued. If you don’t save a bit of your time for you, now, out of every week,’ as she puts it, ‘there is no moment in the future when you’ll magically be done with everything and have loads of free time.’ This is the same insight embodied in two venerable pieces of time management advice: to work on your most important project for the first hour of each day, and to protect your time by scheduling ‘meetings’ with your-self, marking them in your calendar so that other commitments can’t intrude. Thinking in terms of ‘paying yourself first’ transforms these one-off tips into a philosophy of life, at the core of which lies this simple insight: if you plan to spend some of your four thousand weeks doing what matters most to you, then at some point you’re just going to have to start doing it.

Excerpt from: Four Thousand Weeks: Embrace your limits. Change your life by Oliver Burkeman

♦️ IKEA Need Space

💎 Don’t remove a seemingly foolish long-standing custom or institution until you understand its intended purpose

This rule is known as Chesterton’s fence, after G. K. Chesterton, the British writer who proposed it in an essay in 1929. Imagine you discover a road that has a fence built across it for no particular reason you can see. You say to yourself, “Why would someone build a fence here? This seems unnecessary and stupid, let’s tear it down.” But if you don’t understand why the fence is there, Chesterton argued, you can’t be confident that it’s okay to tear it down. Long-standing customs or institutions are like those fences, he said. Naive reformers look at them and say, “I don’t see the use of this; let’s clear it away.” But more thoughtful reformers reply, “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

Excerpt from: The Scout Mindset: The Perils of Defensive Thinking and How to Be Right More Often by Julia Galef

♦️ MTV Switch Off Illegal Downloads

💎 Why seeking perfection may be an imperfect strategy (a Golf lesson)

In golf, perfection is represented by a hole in one. I mean, even I know that. But recently I was fascinated to discover that most professional players don’t aim for that particular metric. Instead, they try to leave the ball stiff: a foot or so beneath the hole. This gives them a chance of an easy putt uphill, whereas if they try to be too precise, there’s a risk they end up above the hole with a more difficult downhill shot.

Occasionally, the ball will go straight in, but this is usually the unintentional result of a bad shot! Likewise, a less accomplished player will sometimes aim for the flag, but any direct hits will be greatly outnumbered by misses. That’s why you’ve never heard of the world record holder for holes in one (Texan player Mancil Davies has achieved 51 but has never got beyond journeyman status because of the erratic nature of his technique).

The point is that the top pros don’t aim for perfection every time. They aim to get 90% of the way there because they know that – over the course of a round, a tournament or a career – this will produce better results than shooting for 100%.

Excerpt from: Go Luck Yourself: 40 ways to stack the odds in your brand’s favour by Andy Nairn

💎 An unintended consequence of Uber

Among other things, Uber has made it far easier for party-goers to get home safely. A study published in 2017 found that after Uber’s arrival in Portland, Oregon, alcohol-related car crashes declined by 62%. But at the same time, the spread of ride-hailing apps may have tempted people to drink to excess, knowing that they won’t beat the wheel. A study published in November 2019 by three economists – Jacob Burgdorf and Conor Lennon of the University of Louisville, and Keith Teltser of Georgia State University – found that the widespread availability of ride-sharing apps had indeed made it easier for the late-night crowd to binge.

By matching data on Uber’s availability with health Surveys from America’s Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, the authors found that on average alcohol consumption rose by 3%, binge drinking (in which a person downs four or five-drinks in two hours) increased by 8%, and heavy drinking (defined as three or more instances of binge drinking in a month) surged by 9% within a couple of years of the ride-hailing company coming to town. Increases were even higher in cities without public transport, where the presence of Uber led average drinking to rise by 5% and instances of binge drinking to go up by around 20%. (heavy drinking still rose by 9%.) Remarkably, excessive drinking had actually been in decline before Uber’s appearance, giving further evidence that the firm’s arrival affected behavior.

Excerpt from: Unconventional Wisdom: Adventures in the Surprisingly True by Tom Standage

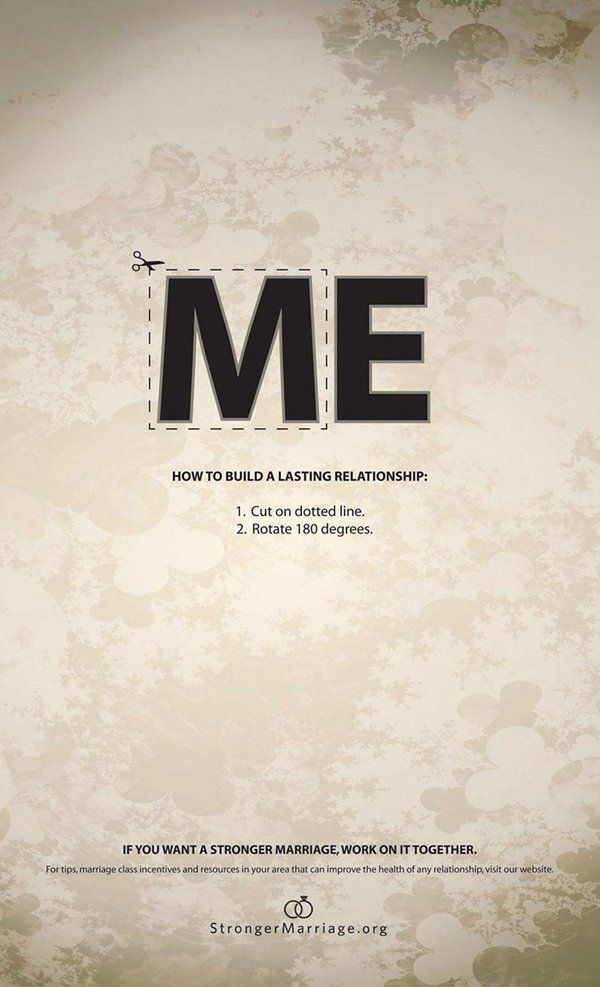

♦️ Stronger Marriage Change Me to We

💎 Social proof – Rolling Stones style

The original manager of the Rolling Stones, Andrew Loog Oldham, acted out his own form of emotional contagion in 1965 , from the back of the theatre where the band would perform. As the band came onstage, he noticed that if he crouched down to be out of sight and screamed in high-pitched voice, then everyone would would scream with him. The rest, as they say, is rock and roll history.

Excerpt from: Tarzan Economics: Eight Principles for Pivoting through Disruption by Will Page

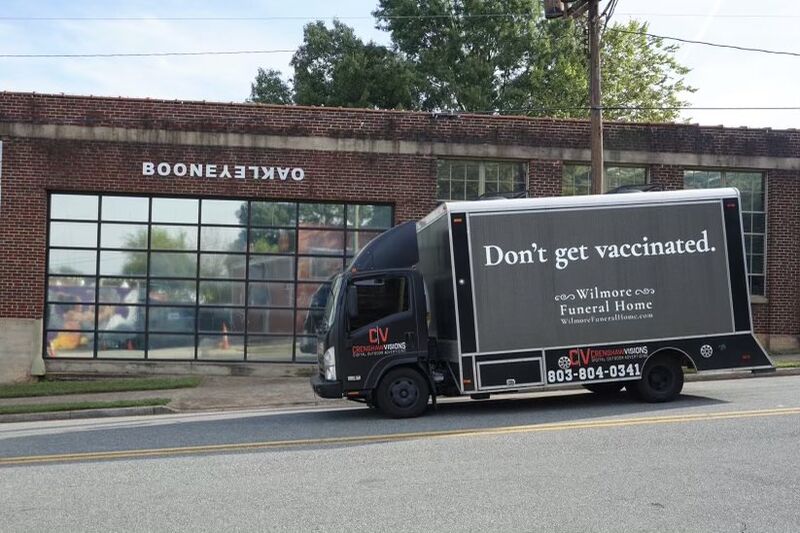

♦️ Wilmore Funeral Home Don’t Get Vaccinated

💎 On the importance of an eclectic mix of stimuli if we’re to have an interesting point of view

Talking of which, another strategist called Russell Davies does a talk on “How to be interesting”. And guess what metaphor he uses – albeit in a very different way?

“We need to have lots of random hooks and loops,” he says. “If we read the same old books, we get to know more about the thing we know lots about already. We need to subscribe to magazines that we wouldn’t normally subscribe to; we need to go to places that we wouldn’t normally go to, eat at places that may not be our kind of place. We stay interesting when we don’t just stay in our groove. We keep pushing; we leave what we know behind for a bit. Velcro goes in many different directions in order to make a connection. If we are interested in new ideas so should we.”

Excerpt from: Go Luck Yourself: 40 ways to stack the odds in your brand’s favour by Andy Nairn

💎 On the danger of taking answers to surveys at face value

to discount with WEIRD logic. “We can ask a consumer what’s most important for them when they pick out an insurance policy, and people will give us the standard answers: it’s the cost, the expected return, the service, that people are friendly, and all of that,” Glottrup said. “But when we pose the second line of questioning-what did you pay in costs last year, what was your return, when was the last time you actually used our service? – people will go blank. They will have no answer [so] these things simply cannot be the reason.”

Excerpt from: Anthro-Vision: How Anthropology Can Explain Business and Life by Gillian Tett

♦️ McDonalds Red Bus / Box Fries

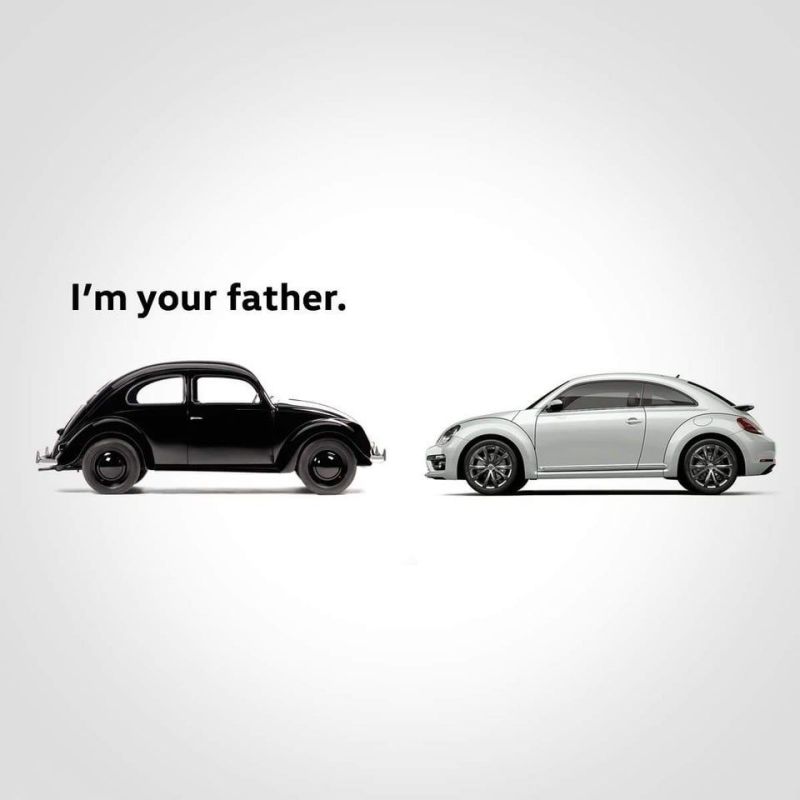

♦️ VW I’m your Father

💎 The law of least effort

A general “law of least effort “applies to cognitive as well as physical exertion. The law asserts that if there are several ways of achieving the same goal, people will eventually gravitate to the least demanding course of action. … Laziness is built deep into our nature.

Excerpt from: Friction: The Untapped Force That Can Be Your Most Powerful Advantage by Roger Dooley

💎 It’s as if the less we know, the more we try and dress things up in complicated sounding terms

Another of the wise men whose voice appears in these pages, the physicist Richard Feynman, once remarked that many fields have a tendency for pomposity, to make things seem deep and pro found. It’s as if the less we know, the more we try to dress things up with complicated-sounding terms. We do this in countless fields, from sociology to philosophy to history to economics – and it’s definitely the case in business. I suspect that the dreariness in so much business writing often stems from wanting to sound as though we have all the answers, and from a corresponding unwillingness to recognize the limits of what we know. Regarding a particularly self important philosopher, Feynman observed:

It isn’t the philosophy that gets me, it’s the pomposity. If they’d just laugh at themselves! If they’d just say, “I think it’s like this, but von Leipzig thought it was like that, and he has a good shot at it, too”.

Excerpt from: The Halo Effect: How Managers let Themselves be Deceived by Phil Rosenzweig

♦️ Volkswagen Precision Parking

💎 Interesting test in Estonia to reduce speeding

Time is money. That, at least, is the principle behind an innovative scheme being tested in Estonia to deal with dangerous driving. During trials that began in 2019, anyone caught speeding along the road between Tallinn and the town of Rapla was stopped and given a choice. They could pay a fine, as usual, or take a ‘timeout’ instead – waiting going when stopped. In other words, they could pay the fine in time rather than money.

The aim of the experiment was to see how drivers perceive speeding, and whether loss of time might be a stronger deterrent than loss of money. The project is a collaboration between Estonia’s Home Office and the police force, and is part of a program designed to encourage innovation in public services. Government teams propose a problem they would like to solve – such as traffic accidents caused by irresponsible driving – and work under the guidance of an innovation unit. Teams are expected to do all fieldwork and interviews themselves.

Excerpt from: Unconventional Wisdom: Adventures in the Surprisingly True by Tom Standage

♦️ Ariel Bright White

💎 Interesting reframing of how much Spotify pay musicians

If we take the UK’s most listened-to radio show- BBC Radio 2’s Breakfast Show – then the songwriter can expect the Performing Right Society for Music expect Phonographic Performance Limited (PPL) to collect roughly £60. Stare at a royalty statement which lists £150 for a spin alongside £0.005 for a stream and you can understand the fear of letting go of the old wine.

But the economics don’t support that fear. A ‘spin’ on BBC Radio 2’s Breakfast Show will reach 8 million people; you need therefore to divide the £150 by the 8 million pairs of ears to get a comparative unit value per listener, and this results in £0.00002 – which is less than half a percent of the £ 0.005 that you would get from one unique person on a streaming service. What’s more, this is not an either/or comparison as those who listen to it on the radio may be more inclined to stream it on Spotify. To bring this calculation full circle, had those 8 million listeners streamed the song on Spotify (which is not beyond the realms of possibility), a cheque of £40,000 would be paid across to the artist and songwriter – not £150. ‘Not too shabby’ as some Americans like to say.

Excerpt from: Tarzan Economics: Eight Principles for Pivoting through Disruption by Will Page

💎 How testing in unnatural environments backfires

If you’ve ever wondered why every poster and every trailer and every TV spot looks exactly the same, it’s because of testing. It’s because anything interesting scores poorly and gets kicked out Now I’ve tried to argue that the methodology of this testing doesn’t work. If you take a poster or a trailer and you show it to somebody in isolation, that’s not really an accurate reflection of whether it’s working because we don’t see them in isolation, we see them in groups. We see a trailer in the middle of five other trailers, we see a poster in the middle of eight other posters, and I’ve tried to argue that maybe the thing that’s making it distinctive and score poorly actually would stick out if you presented it to these people the way the real world presents it. And I’ve never won that argument.

♦️ Colgate Attack the Enemy