Author: David Greenwood

💎 On the power of prestige (name versus quality)

Of the twelve journals, only three spotted that they had already published the article. This was a grave lapse of memory on the part of the editors and their referees, but then memory is fallible; however, worse was to come. Eight out of the remaining nine articles, all of which had been previously published, were rejected. Moreover, of the sixteen referees and eight editors who looked at these eight papers, every single one stated that the paper they examined did not merit publication. This is surely a startling instance of the availability error. It suggests that in deciding whether an article should be published, referees and editors pay more attention to the authors’ names and to the standing of the institution to which they belong than they do to the scientific work reported.

Excerpt from: Irrationality: The enemy within by Stuart Sutherland

♦️ WWF Attention to Global Warming

💎 On the secret behind the world’s first aspirational root vegetable (scarcity)

Scarcity is a great way to make something seem more attractive and valuable. The Blues Brothers famously played ‘for one night only’ and Bernd Pichetsrieder, the great BMW marketing guru insisted on ‘always selling one less than you can’.

This kind of strategy is sometimes called the ‘velvet rope’ – ‘you can’t come in’ often makes something that much more appealing. This was also the trick behind the story of how Frederick the Great turned Prussia into a potato eating nation – he insisted that no-one but the nobility could eat the potato. The ‘aspirational’ root vegetable? Believe it.

Excerpt from: Copy, Copy, Copy: How to Do Smarter Marketing by Using Other People’s Ideas by Mark Earls

♦️ Pringles Hot Spicy

💎 On the tendency to interpret information to fit with our own behaviour (smoking and lung cancer)

My personal favourite from Festinger’s many brilliant examples of cognitive dissonance deals with people’s beliefs about the link between smoking and lung cancer. He was writing at the very birth of research on the causes of cancer. It was a unique window of time during which it was possible to test whether groups of smokers and non-smokers would accept or reject new information that had been uncovered about a link. Festinger saw the effects you’d expect from anyone suffering cognitive dissonance: heavy smokers – those who had the most to lose from the new research being right – were the most resistant to believing that a link had been proven; only 7 per cent accepted the validity of the new research. Twice as many moderate smokers accepted the link, at 16 per cent. Non-smokers were much more willing than smokers to believe the link had been proven, but as a mark of just how far social norms have swung since then, only 29 per cent of them believed the link had been proven, despite having nothing to lose.

Excerpt from: The Perils of Perception Why We’re Wrong About Nearly Everything by Bobby Duffy

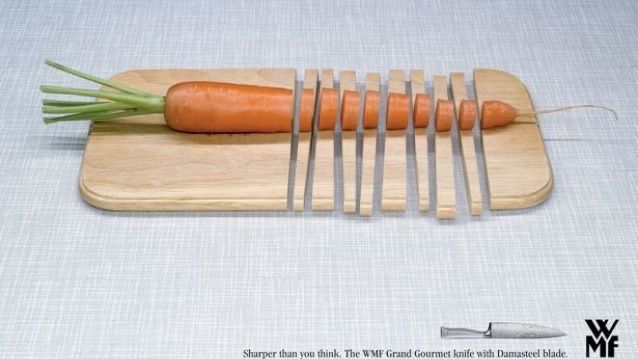

♦️ WMF Sharper than you think

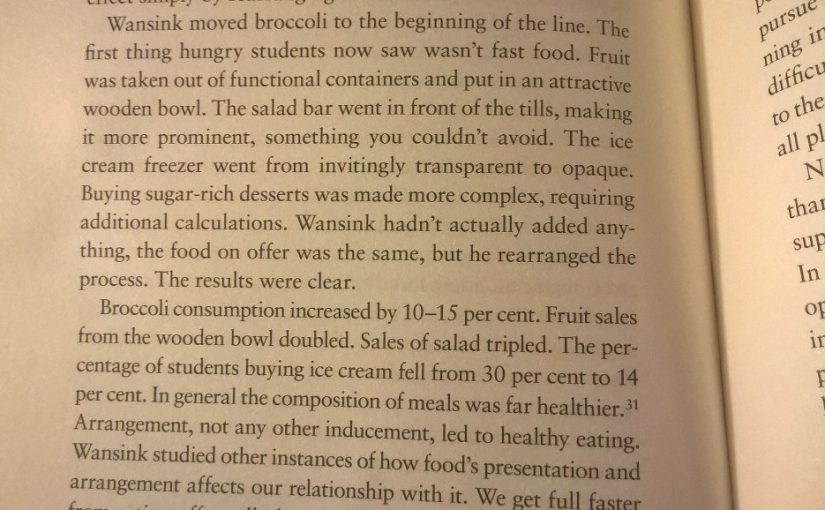

💎 On the power of choice architecture in determining what we eat (eat your Broccoli, kids)

Wansink moved broccoli to the beginning of the line. The first thing hungry students now saw wasn’t fast food. Fruit was taken out of functional containers and put in an attractive wooden bowl. The salad bar went in front of the tills, making it more prominent, something you couldn’t avoid. The ice cream freezer went from invitingly transparent to opaque. Buying sugar-rich desserts was made more complex, requiring additional calculations. Wansink hadn’t actually added anything, the food on offer was the same, but he rearranged the process. The results were clear.

Broccoli consumption increased by 10-15 per cent. Fruit sales from the wooden bowl doubled. Sales of salad tripled. The percentage of students buying ice cream fell from 30 per cent to 14 per cent. In general the composition of meals was far healthier. Arrangement, not any other inducement, led to healthy eating. Wansink studied other instances of how food’s presentation and arrangement affects our relationship with it.

Excerpt from: Curation: The power of selection in a world of excess by Michael Bhaskar

💎 On the power of personalised messages (especially images)

Recently, the Behavioural Insights Team began altering the letter sent to British citizens if they failed to pay taxes on their car. The traditional letter was all text, informing the subject that if they didn’t pay now they would be hit with various penalties, including a clamped or and hefty fines. To increase the effectiveness of the letter, the scientists began experimenting with various forms of personalization. The first variant involved making a more specific threat, telling recipients that they would lose their particular model of car if they didn’t pay the tax. The second variant featured a personalized visual, so that the letter came attached with a photograph of the actual car question. While both approaches increased compliance, the customized picture was the most effective—it increased the compliance rate from 40 to 49 percent.

Excerpt from: The Smarter Screen: Surprising Ways to Influence and Improve Online Behavior by Shlomo Benartzi and Jonah Lehrer

♦️ Social Distancing at the Opticians

💎 On spending money we’ve been gifted (influence on overall spending)

About thirty years ago, an economist at the Bank of Israel named Michael Landsberger undertook a study of a group of Israelis who were receiving regular restitution payments from the West German government after World War II. Although these payments could without exaggeration be described as blood money – inasmuch as they were intended to make up for Nazi atrocities – they could also fairly accurately be described as found money. Because of this, and because the payments varied significantly in size from one individual or family to another, Landsberger was able to gauge the effect of the size of such windfalls on each recipients spending rate. What he discovered was amazing. The group of recipients who received the larger payments (which were equal to about two-thirds of their annual income) had a spending rate of about 0.23. In other words, for every dollar they received, their marginal spending increased by 23 percent; the rest was saved. Conversely, the group that received the smallest windfall payments (equal to about 7 percent of annual income) had a spending rate of 2. Or, more accurately, for every dollar of found money, they spent $1 of found money and another $1 from “savings” (what they actually saved or what they might have saved).

♦️ Vaseline Soothing Powers

💎 On going that little bit further than the competition to tip the pitch odds in your favour (personalisation can win the deal)

In 2005 a flagging Japanese economy convinced Takashi Hashiyama, president of the electronics firm Maspro Denkoh, to sell the corporate collection of French impressionist paintings This included a major Cezanne landscape and lesser works by Sisley, van Gogh, and Picasso. Both Christies and Sotheby’s gave presentations to Hashiyama touting their expertise and ability to achieve the highest auction prices. In Hashiyama’s judgment, the presentations were equally convincing. To settle the matter, he proposed a game of rock, paper, scissors.

“The client was very serious about this,” Christie’s deputy chairman Jonathan Rendell said, “so we were very serious about it, too.” The money was serious, too. The Maspro Denkoh collection was valued at $20 million. Both Christie’s and Sotheby’s quickly agreed to the game.

In contrast, Kanae Ishibashi, the president of Christie’s Japan, began researching RPS strategies on the Internet. You may or may not be surprised to learn that an awful lot has been written on the game. Ishibashi had a break when Nicholas Maclean, Christie’s director of impressionist and modern art, mentioned that his eleven-year-old twin daughters, Alice and Flora, played the game at school almost daily.

Alice’s advice was “Everybody knows you always start with scissors.” Flora seconded this, saying “Rock is way too obvious… Since they were beginners, scissors was definitely the safest.”

Both girls also agreed that, in the event of a scissors-scissors tie, the next choice should be scissors again — precisely because “everybody expects you to choose rock.”

Ishibashi went into the meeting with this strategy, while the Sotheby’s rep went in with no strategy at all. The auction house people sat facing each other at a conference table, flanked by Maspro accountants. To avoid ambiguity, the players wrote their choices on a slip of paper. A Maspro executive opened the slips. Ishibashi had chosen scissors, and the Sotheby’s representative had chosen paper. Scissors cuts paper, and Christie’s won. In early May 2005, Christie’s auctioned the four paintings for $17.8m, earning the auction house a 1.9m commission.

Excerpt from: How to Predict the Unpredictable: The Art of Outsmarting Almost Everyone by William Poundstone

💎 On social proof being a helpful shortcut (best-seller lists)

So we use others as a helpful shortcut. A filter. If a book is on the best-seller list, we’re more likely to skim the description. If a song is already popular, we’re more likely to give it a listen. Following others saves us time and effort and (hopefully) leads us to something we’re more likely to enjoy.

Does that mean we’ll like all those books or songs ourselves? Not necessarily. But we’re more likely to check them out and give them a try. And given the thousands of competing options out there, this increased attention is enough to give those items a boost.

Knowing others liked something also encourages people to give it the benefit of the doubt. Appearing on the best-seller list provides an air of credibility.

Excerpt from: Invisible Influence: The Hidden Forces That Shape Behavior by Jonah Berger

♦️ Braun Oral B Sweep

💎 On our tendency to seek news that confirms what we already know (we get uncomfortable with new things)

Be careful. People like to be told what they already know. Remember that. They get uncomfortable when you tell them new things. New things . . . well, new things aren’t what they expect. They like to know that, say, a dog will bite a man. That is what dogs do. They don’t want to know that man bites a dog, because the world is not supposed to happen like that. In short, what people think they want is news, but what they really crave is olds … Not news but olds, telling people that what they think they already know is true.

—Terry Pratchett through the character Lord Vetinari from his The Truth: A Discworld Novel

♦️ KitKat Have a break (from social media)

💎 On our present preference bias (to boost pension saving rates)

The ‘Save More Tomorrow’ programme tackles both of these barriers head-on by, first, auto-enrolling people onto workplace saving schemes to combat inertia. People are obviously completely free to opt back out, but, human nature being what it is 90 per cent stay on the scheme, with their inertia now working for them rather than against them. An auto-escalator then ups the contributions, not immediately but over time (the tomorrow bit). This shifted the reluctant hugely: when asked whether they would up their contributions now by five percentage points, most said no (we need the chocolate now). But when asked whether they’d commit to saving more in the future, 78 per cent said yes.

The impact of ‘Save More Tomorrow’ has been substantial. Before the programme, the average saving rate for workers in the sample was 3-5 per cent, but after four years this had increased nearly four-fold to 13.6 per cent.

Excerpt from: The Perils of Perception Why We’re Wrong About Nearly Everything by Bobby Duffy

💎 On new and revolutionary products (our opinions of them change as we age)

There’s a set of rules that anything that was in the world when you were born is normal and natural. Anything invented between when you were 15 and 35 is new and revolutionary and exciting, and you’ll probably get a career in it. Anything invented after you’re 35 is against the natural order of things.

Excerpt from: Paid Attention: Innovative Advertising for a Digital World by Faris Yakob

♦️ Coffee It always works

💎 On resisting the impulse to tinker with marketing approaches (paying not to change)

There was a perhaps apocryphal tale about a time when Reeves was out sailing with a client. The client made bold to ask why he should continue paying the same fee when the ad was never really changed. “What do you need all those people on my account when you never do anything?” Reeves, who could be surly, gruffed, “To keep your people from changing what I’ve done.”

Excerpt from: Branded Nation: The Marketing of Megachurch. College Inc.. and Museumworld by James Twitchell

♦️ Ford Mustang Required to View

💎 On the risk of unintended consequences (because of moral licensing)

Before starting out on this change of venue, they first collected data on the amount of paper hand towels used in the mens restroom for a period of 15 days to work out the average amount of paper towels typically used each day. Once this had been done they then introduced a large recycling bin near the sinks with signs indicating that the restrooms were participating in a paper hand towel recycling program, and that any used hand towels placed in the bin would be recycled. For the next 15 days, they then simply measured the amount of paper hand towels used.

Consistent with their laboratory studies, paper towel usage increased after the introduction of the recycling bin by an average of half a paper towel per person. At first glance this small increase doesn’t seem that big a deal. However, given that the restroom was typically used over a hundred times each work day, the increase in usage was substantial: It totaled about 12,500 paper hand towels annually for this one restroom alone.

Excerpt from: The Small BIG: Small Changes that Spark Big Influence by Robert Cialdini, Noah Goldstein, and Steve Martin

💎 On the evolutionary benefit of self-deception and lying (finding a mate)

Evolutionary biologist Robert Trivers wanted to persuade a potential mate or ally of their good intentions would be better at it if they could deceive themselves without ‘leakage’ of knowledge or intent; and the most efficient way to simulate truth-telling would be to erase internal awareness of the deception. The best liars would be those who were better at lying to themselves because they would actually believe their own deceptions when they made them. They would be more likely to survive and pass on their genes; hence our gift for self-deception.

Excerpt from: Born Liars: Why We Can’t Live Without Deceit by Ian Leslie

♦️ New King Hot Pepper Sauce

💎 On the need to be wary of the motivations of those offering us advice (even “impartial” outsiders)

Auditors provide a good example of this bias. One hundred thirty-nine professional auditors were given five different auditing cases to examine. The cases concerned a variety of controversial aspects of accounting. For instance, one covered the recognition of intangibles, one covered revenue recognition, and one concerned capitalization versus expensing of expenditures. The auditors were told the cases were independent of each other.

The auditors were randomly assigned to either work for the company or work for an outside investor who was considering investing in the company in question. The auditors who were told they were working for the company were 31 percent more likely to accept the various dubious accounting moves than those who were told they worked for the outside investor. So much for an impartial outsider—and this was in the post-Enron age!

Excerpt from: The Little Book of Behavioral Investing: How not to be your own worst enemy by James Montier

♦️ Johnnie Walker There’s a Reason Why he Walks

💎 On the various ways in which social proof affects us (obesity is contagious)

Obesity is contagious. If your best friends get fat, your risk of gaining weight goes up.

Broadcasters mimic one another, producing otherwise inexplicable fads in programming. (Think reality television, American Idol and its siblings, game shows that come and go, the rise and fall and rise of science fiction, and so forth.)

The academic effort of college students is influenced by their peers, so much so that the random assignments of first-year students to dormitories or roommates can have big consequences for their grades and hence on their future prospects. (Maybe parents should worry less about which college their kids go to and more about which roommate they get.)

In the American judicial system, federal judges on three-judge panels are affected by the votes of their colleagues. The typical Republican appointee shows pretty liberal voting patterns when sitting with two Democratic appointees, and the typical Democratic appointee shows pretty conservative voting patterns when sitting with two Republican appointees. Both sets of appointees show far more moderate voting patterns when they are sitting with at least one judge appointed by a president of the opposing political party.

Excerpt from: Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein

💎 On the importance information gaps in stories (curiosity)

Stories depend on the artful manipulation of what Loewenstein calls information gaps. In McKee’s words, ‘Curiosity is the intellectual need to answer questions and close open patterns. Story plays to this universal desire by doing the opposite, posing questions and opening situations.’ The storyteller plays a cat and mouse game with the viewer (or reader, or listener), opening and closing information gaps as the narrative unfolds, unspooling the viewer’s curiosity.

Excerpt from: Curious: The Desire to Know and Why Your Future Depends on It by Ian Leslie

♦️ Nivea Stay Original