In 1973, Standing conducted a range of experiments exploring human memory. The participants were shown pictures or words and instructed to pay attention to them and try to memorize them for a test on memory. Each picture or word was shown once, for five seconds.

The words had been randomly selected from the Merriam-Webster dictionary and were printed on 35mm slides – words like ‘salad’, ‘cotton’, reduce’, ‘camouflage’ ‘ton’.

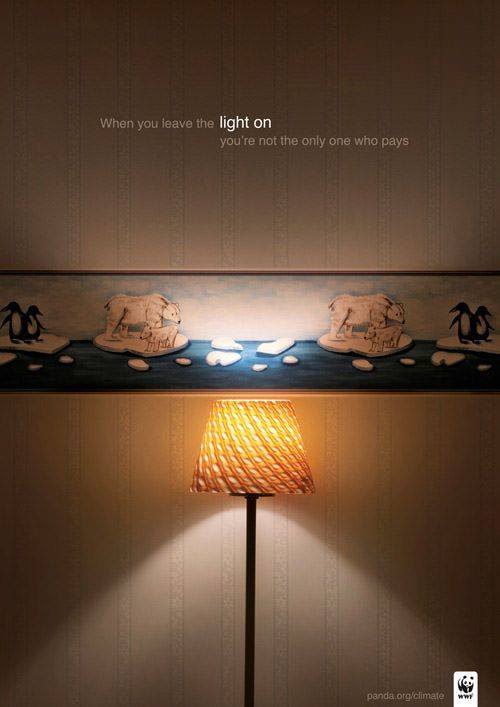

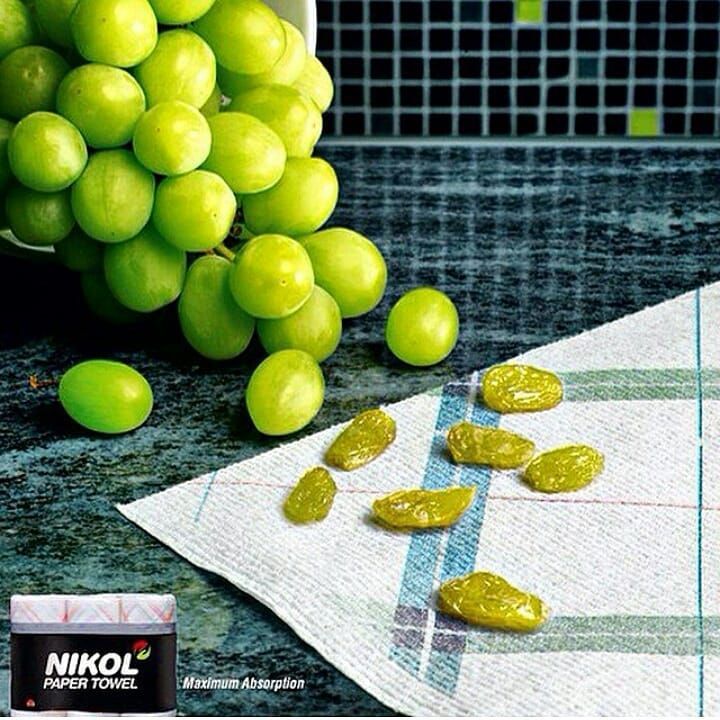

The pictures were taken from 1,000 snapshots – most of them from holidays – beaches, palm trees, sunsets – volunteered by the students and faculty at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada, where Standing taught at the time. But some of the pictures were more vivid – a crashed plane, for instance, or a dog holding a pipe. But remember this was the seventies – all dogs smoked pipes back then.

Two days later the participants were shown a series of two snapshots or two words at a time, one from the stack of snapshots they had seen before and one new, and were asked which one looked more familiar.

The experiment showed that our picture memory is superior to our verbal memory. When the learning set is 1,000 words selected from the dictionary above, we remember 62 per cent of them, while 77 per cent of the 1,000 selected snapshots were remembered. The bigger the learning set, the smaller the recognition rate. So, for instance, if the learning set for pictures were increased to 10,000, the recognition rate dropped to 66 per cent. However, we remember snapshots better than we do words. That may be why you might be better at remembering faces than names. So, if you are introduced to Penelope, it might help you remember her name if you picture Penelope Cruz standing next to her.

In addition, if more vivid pictures were presented, rather than the routine snapshots, recognition jumped to 88 per cent for 1,000 pictures.